One Step Before Happiness serie-Text by Berna Valada

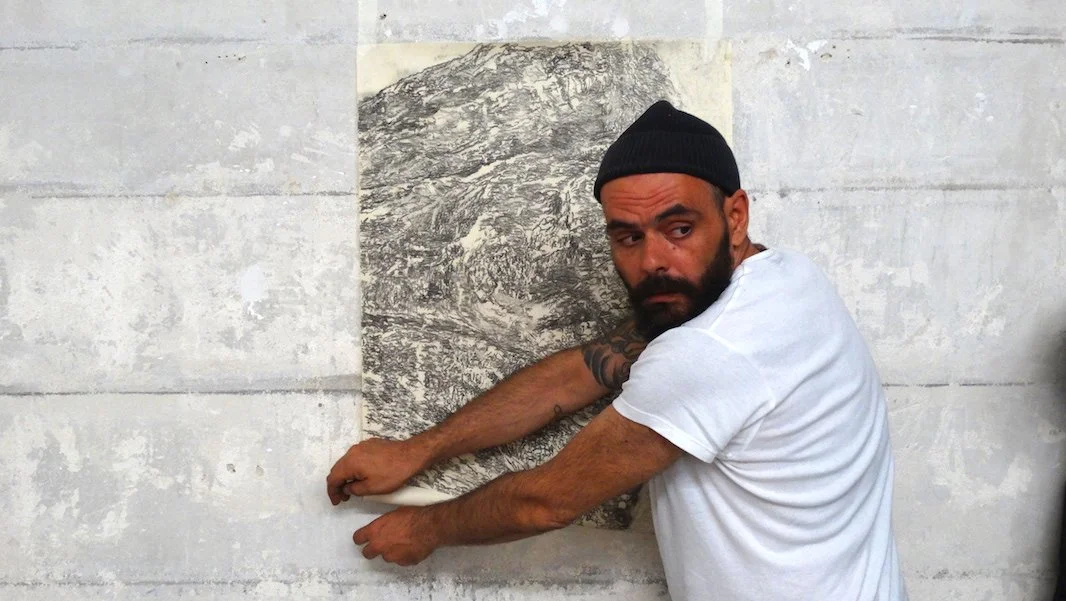

In One Step Before Happiness, Jorge Da Cruz turns to the mountain—not merely as a feature of terrain, but as a vessel of meaning. For millennia, mountains have been regarded as sacred thresholds, places where earth touched the divine. They embodied endurance and grandeur, forming a symbolic bridge between human life and what lay beyond it. In these drawings, that symbolic charge has shifted. The mountain no longer radiates transcendence; it appears worn, stripped of aura, and recast as a challenge to overcome rather than a site to revere.

These imagined landscapes speak not of presence, but of its fading. If climbers appear, they do not ascend in search of communion; they climb from restlessness, drive, or defiance. The mountain becomes a goal—a metric of achievement. The land, in turn, carries the marks of that exchange: deep trails etched by repetition, disrupted ecologies, and a quiet erosion of meaning. The works register this shift without declaring it; they show how conquest can replace reverence, and how that substitution changes both the land and our perception of it.

Charcoal—raw, dry, elemental—is central to the series’ language. It invites building and erasure, weight and air, grain and silence. Da Cruz uses it to conjure terrains that do not shine so much as loom. Edges soften into memory; peaks hold themselves back. The drawings refuse spectacle. Instead, they ask us to inhabit gradations of dark and light, to feel the pull of mass without the promise of revelation. Charcoal’s dust becomes a kind of weather—settling on surfaces, filling crevices, turning light into haze—so that form appears as if recovered rather than asserted.

The work takes shape as a group of charcoal drawings in different sizes. This variation in scale is not incidental; it guides how we move through the series and what we notice. Larger works open onto distance, gathering horizon lines and atmospheric breadth; smaller works pull us close, insisting on surface, touch, and the micro-geographies of cracks, grooves, and shadowed grain. As the eye travels between scales, the image itself seems to transform: what begins as landscape shifts into texture; what reads as symbol turns tactile. The mountain does not disappear—it changes register. Vastness becomes intimacy; meaning becomes matter.

Yet One Step Before Happiness resists nostalgia. It does not mourn a lost world of myth, nor does it propose a return to it. Instead, it lingers at the edge, in the charged interval before something changes. Each drawing feels like a held breath, a pause saturated with tension and potential. The title keeps the balance unstable: is this one step before happiness, or one step before collapse? The work does not decide; it inhabits the interval. That undecidability is not a weakness but a method—an insistence that perception itself is a threshold, and that our responsibilities to the world begin there.

What remains is a quiet invitation to look more closely. Even without their myths, mountains retain force. They ask for attention, humility, and responsibility. They remind us of the distance between what we once believed and what we now practice—and of the fragile, unfinished bond that still binds reverence to care. In Da Cruz’s hands, charcoal becomes a tool for thinking with matter: how meaning accumulates, how it erodes, and how, even in erosion, something persists.

These drawings do not offer solutions. They offer a stance: to meet the mountain without the promise of transcendence, and to keep looking anyway. To accept that the land records our choices. To recognize that the interval before change—the threshold where we are held—is where perception, and perhaps accountability, begins. In that sense, One Step Before Happiness is less a declaration than a proposition: that the space between reverence and responsibility is still open, and that how we see will shape how we live with what stands before us. BV

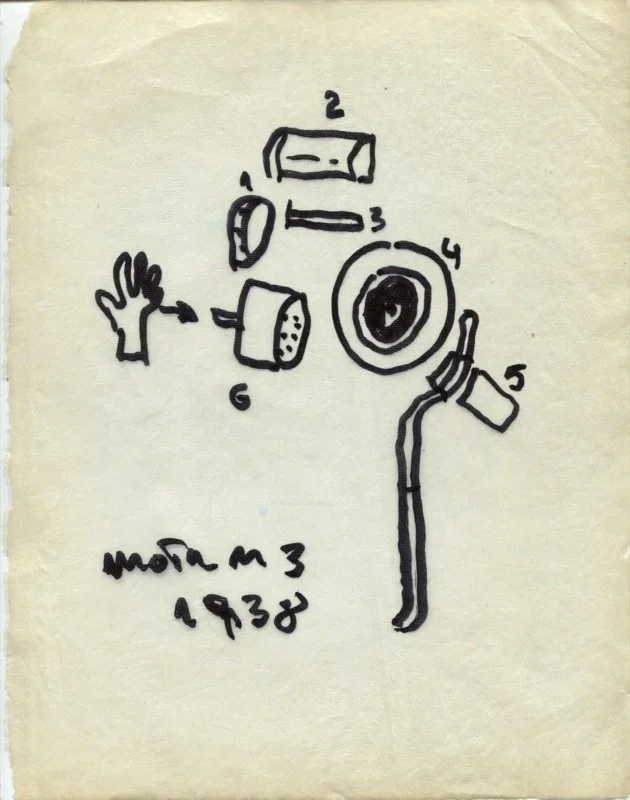

Plans to Build a Boat

The idea for this piece started with a chance find at a flea market in Berlin. I came across this small, handmade photo album from 1937—nothing flashy, just something someone had clearly taken care to put together. Inside were photos of a family spending weekends by a lake. They were simple, quiet moments—full of ease, joy, and connection. I didn’t know anything about the people in the pictures, but something about the mood of those images really hit me.

At the time, my own life in Berlin looked very different—intense, fast, a little chaotic. I was deep in a kind of Dionysian, isolating way of living, and seeing those photographs felt like staring into another reality altogether. That contrast—between the raw, restless energy I was living in and the calm steadiness of the people in those images—sparked a question in me:

If I had to build a boat with no experience, no plan—just the desire to leave—what would that look like?

That question became the seed for Plans to Build a Boat. It’s not really about a boat in the literal sense. It’s about imagining what it takes to step away from one version of life and move toward another—about gathering the pieces, even without certainty, and beginning to shape a path forward.

The work is still in progress, unfolding slowly as I continue to sit with that question and what it means to build something out of longing, memory, and the need for change.

Jorge

After Cana (“The Great Arrival / The World Creation”), 2018

After Cana (“The Great Arrival / The World Creation”), 2018

Carvão sobre papel, 240 × 300 cm (composto por dezasseis folhas)

Coleção: Enter Foundation

(in portuguese)

O desenho de Jorge Da Cruz pode ser lido como um ato silencioso de sabotagem ao Casamento em Caná de Paolo Veronese. A tela de 1563 de Veronese é um desfile de abundância renascentista — arquitetura em patamares, talheres dourados, convidados em sedas e, acima de tudo, o milagre que transforma água humilde em vinho nobre. Da Cruz mantém a longa mesa do banquete e a multidão cosmopolita, mas esvazia-lhes a jubilação. Aqui o milagre inverte-se: a água sobe em vez de recuar, irrompendo pelo canto inferior esquerdo, ondulando sobre o pavimento de tesselas e roçando as botas dos músicos. Alguns convivas retesam-se; a maioria ergue os copos, determinada a permanecer dentro da ilusão do festim.

A própria superfície participa no drama. Dezasseis folhas independentes justapõem-se, formando uma grelha ténue que fende a imagem como o craquelê de uma faiança antiga. Essas emendas denunciam a construção da obra, sugerindo quão facilmente a cena — e, de facto, qualquer ordem social — pode desfazer-se. No centro superior, uma inesperada faixa de papel em branco abre-se para o céu: uma pausa pálida onde três pequeninas aves descrevem círculos sobre telhados distantes. O vazio soa quase mais alto do que o carvão denso abaixo — um fôlego suspenso antes de a cheia concluir a sua ascensão.

Os negros arroxeados e cinzentos calcários do carvão substituem os óleos opulentos de Veronese. O pó assenta como cinza, suavizando as figuras até que os rostos parecem pairar entre presença e apagamento. Um brilho cintila no bordo de um cálice ou numa manga branca, mas vacila, instável, como lâmpadas de emergência quando a rede falha. Colunas traçadas em vigorosos veios verticais ainda se erguem em cada flanco, mas mesmo esses sentinelas de pedra parecem porosos, manchados pela humidade.

Surge assim uma alegoria da abundância frágil. O banquete parece generoso, mas os seus alicerces — arquitetónicos, ecológicos, espirituais — estão a ceder. Da Cruz não se limita a ilustrar a ansiedade climática (embora a água invasora torne este subtexto difícil de ignorar). Ele investiga a fissura psicológica entre celebração e pressentimento: o nosso talento para rejubilar enquanto o soalho range, para brindar à prosperidade quando a cheia já nos chega aos tornozelos. After Cana convida o público a deter-se nesse intervalo inquieto — entre ritual e rutura — e a perguntar-se por quanto tempo qualquer cultura consegue sustentar a festa quando os próprios elementos da vida, a água e a luz, fogem ao controlo.

Berna Valada, 2021

The Wedding Feast at Cana, Paolo Veronese, 1563

The World Creation 2018. Jorge Da Cruz (n. 1974

Notes for Resonance of Ruin

see more

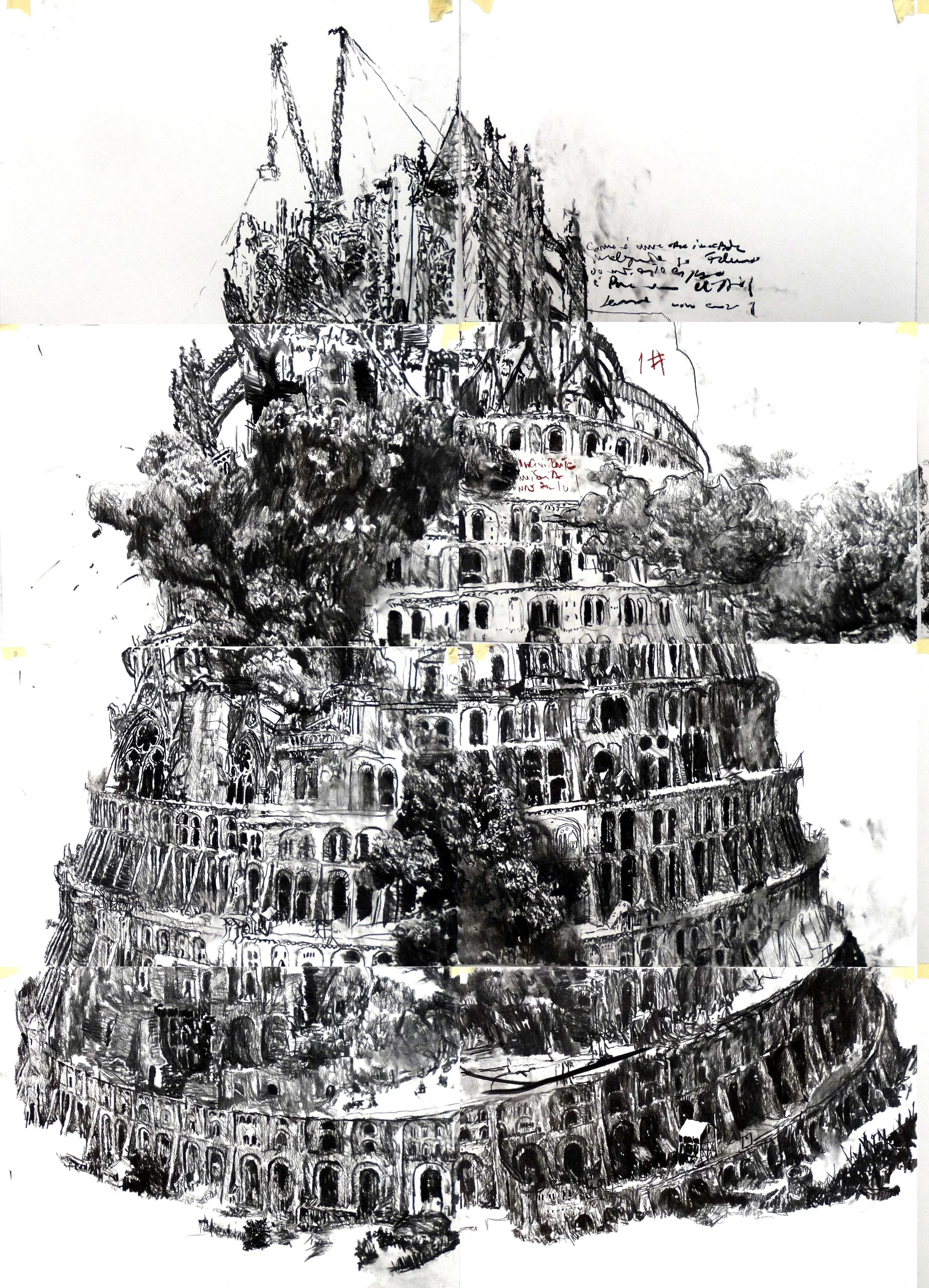

Deconstructing Babel through Charcoal is a quiet reflection on the myth of the Tower of Babel—on ambition, collapse, and the way its story still speaks to the present. Jorge Da Cruz draws from the visual world of Pieter Brueghel the Elder, reimagining that iconic structure through a contemporary lens. With charcoal as his medium, he creates a space where history and now sit side by side.

At the center of the series is the tower—fragile, layered, and built from a mix of styles and times. It looks as if it’s been rebuilt again and again. Each level carries signs of effort and exhaustion, as though every reach toward the sky carries the weight of earlier attempts. The drawing is intricate but never showy, dense with marks that speak to the slow, determined labor behind human ambition.

Charcoal isn’t just the material—it’s part of the message. Its textures shape both the atmosphere and the structure itself. The tower has a softness to it, almost unstable, while darker areas hold it down, giving it weight. Below, water spreads quietly, and small boats drift through it—like pieces of what’s been left behind. They might be fragments of survival, or quiet gestures of retreat.

But this isn’t about destruction. It’s about what holds on. The work looks at the rhythm of building and undoing—how histories, both personal and collective, pile up in layers. It asks us to sit with the limits of our intentions, and to consider how fragile any shared meaning can be.

Resonance of Ruin doesn’t try to retell the myth. It steps inside it. There’s no neat conclusion—just a space to reflect. On failure. On repetition. And on the human urge to keep making, shaping, reaching—especially in the shadow of what we’ve already lost.

Drawing Notes from the Far Side of the Moon

Though Earth and the Moon are in constant motion—rotating and orbiting in a cosmic rhythm—there is a persistent mystery that continues to fascinate: we never see the far side of the Moon from Earth. This phenomenon, often referred to poetically as the “dark side” of the Moon (though it receives as much sunlight as the near side), is not the result of shadow or secrecy, but of a unique orbital condition known as synchronous rotation or tidal locking. The Moon rotates on its own axis at precisely the same rate that it orbits Earth—about once every 27.3 days. This synchronized rotation means that the same hemisphere of the Moon always faces Earth, while the opposite hemisphere remains hidden from direct view. This alignment isn’t coincidental; it’s the result of gravitational forces that, over millions of years, slowed the Moon's rotation to match its orbit. The Earth’s gravitational pull created tidal bulges on the Moon, and the friction from these bulges gradually altered its spin until it settled into this locked, harmonious state.

Despite this locking, the Moon does not appear absolutely still from our perspective. Because of a slight wobble known as libration, we can actually glimpse up to 59% of the lunar surface over time—but never the full 100%. The remaining unseen region—the far side—was entirely unknown until 1959, when the Soviet spacecraft Luna 3 transmitted the first grainy images of this hidden terrain. What it revealed was striking: unlike the familiar face of the Moon, marked by large, dark plains known as maria (from the Latin word mare, meaning “sea”), the far side is rugged, mountainous, and heavily cratered. It is geologically distinct, less touched by ancient volcanic flows, and far more enigmatic.

see more

One Step Before Happiness

In this series, Jorge Da Cruz turns to the mountain as a recurring form—once revered as sacred, now bearing the traces of exile, ambition, and decline. One Step Before Happiness reflects on the transformation of landscapes once associated with divinity. The mountains, which in ancient mythology connected earth and sky, now stand as silent witnesses to a world distanced from transcendence.

Charcoal becomes the ideal medium for this vision: dry, granular, elemental. Through it, Da Cruz constructs vast, desolate terrains. The peaks no longer radiate glory; they loom, marked by absence. Their outlines suggest former grandeur but are softened by erosion, memory, and silence. These are not heroic summits to be conquered, but spaces heavy with meaning—echoes of a lost order.

In this imagined landscape, nature no longer speaks the language of the gods. The climbers who ascend these heights—modern figures of restlessness and defiance—do not seek communion but conquest. The ascent becomes a gesture of hubris, disconnected from the reverence that once shaped our relationship to the land. The mountains, in turn, bear the scars of this shift: weathered trails, disrupted ecologies, a quiet erosion of meaning.

Yet Da Cruz’s work resists nostalgia. The series does not mourn what is lost, but lingers in the space just before transformation. There is still tension—still time. Each drawing is a pause, a threshold: one step before happiness, or perhaps one step before collapse. The title itself holds that ambiguity.

What remains is a call to perception. The mountains, even stripped of myth, retain their force. They demand attention—not only as forms in space, but as symbols of the distance between what we once believed and what we now inhabit. Through this visual language, Da Cruz invites reflection on our place within the landscape, and on the fragile, unfinished bond between reverence and responsibility.

see more

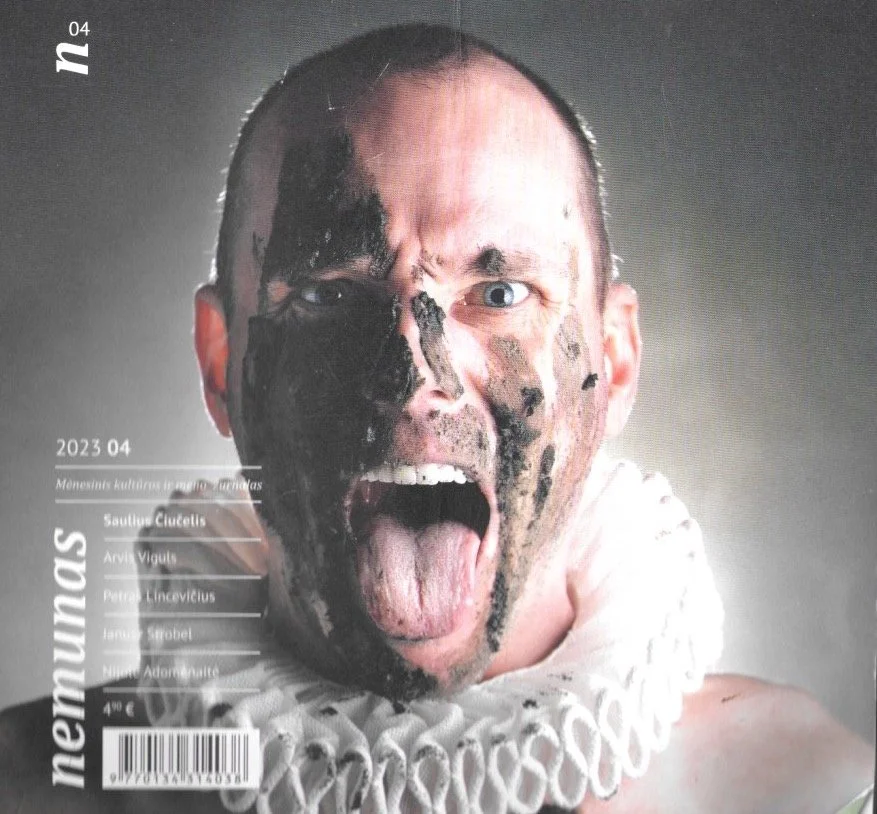

Lithuanian magazine Nemunas (Issue 2023/04) Drawings by JorgedaCruz

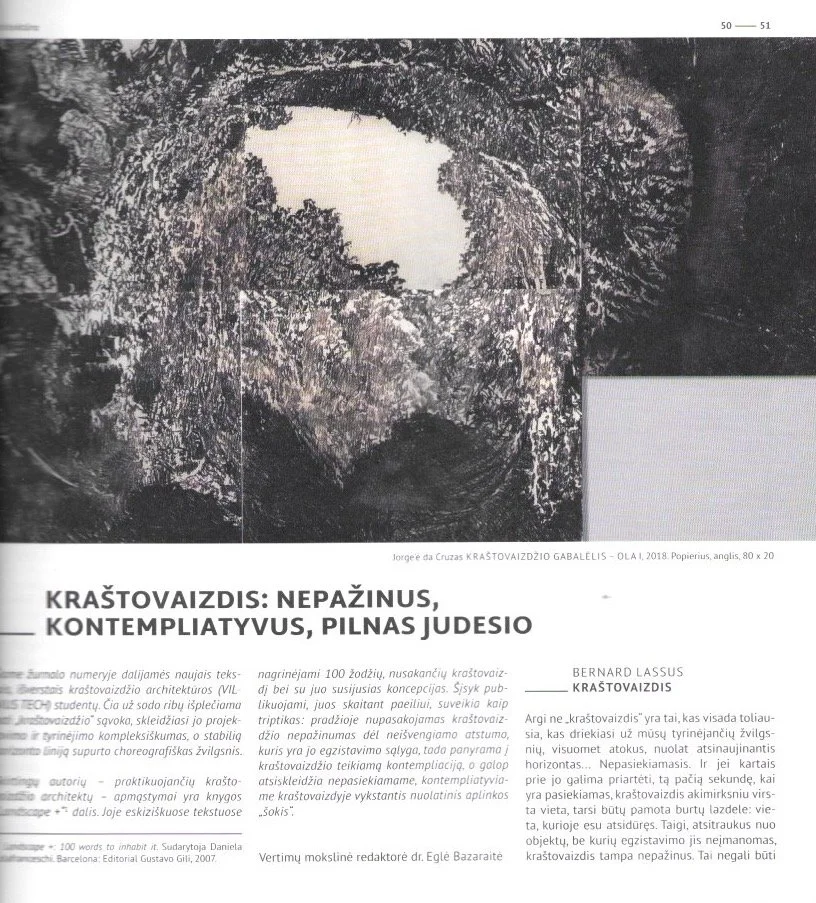

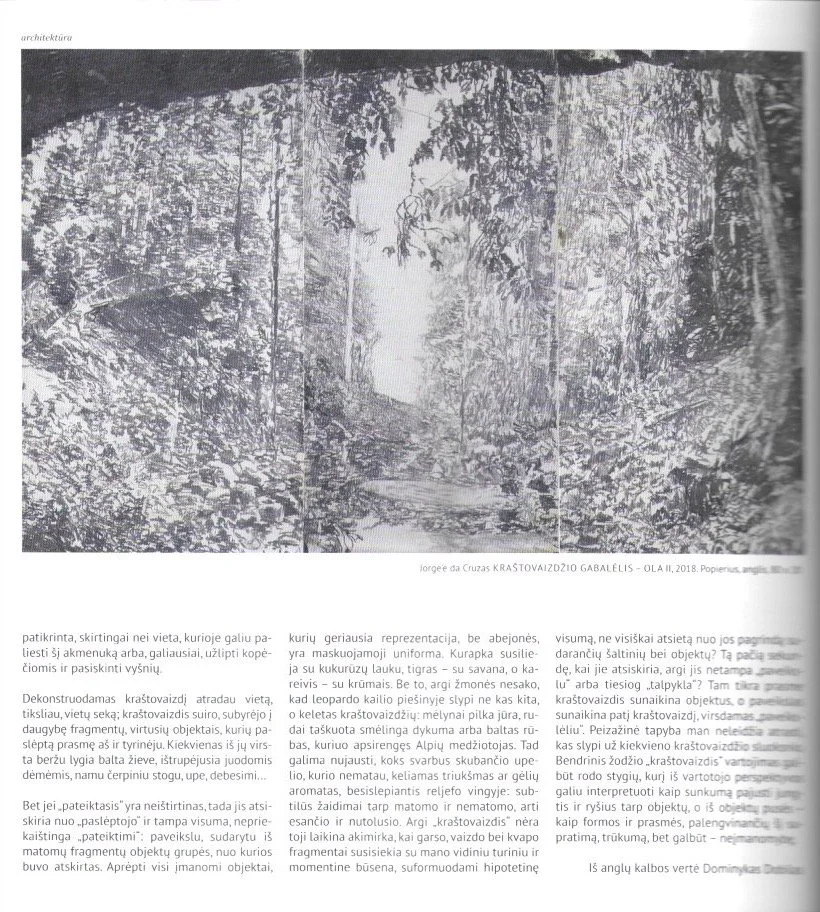

LANDSCAPE: UNKNOWN, CONTEMPLATIVE, FULL OF MOVEMENT

Bernard Lassus – LANDSCAPE

The word "landscape" seems to refer to something always distant, viewed from a traveler’s perspective—always remote, barely accessible. But it’s also mysterious. Sometimes it’s a place one can approach, reach, and even physically touch—a stone path or a cherry tree reached by a ladder. As I deconstructed the landscape, I discovered not a single place but a sequence of places; the landscape disintegrated into a multitude of fragments, objects with hidden meanings that had to be studied. Each was as peculiar as the bark of a birch tree, a red tile roof, a river, or a cloud. But if the "depicted" landscape is not reliable, it separates from the "real" one and becomes a whole, an impeccable representation—an image constructed from a group of visible object fragments that were once part of it. We can try to include every imaginable object: a camouflaged soldier, a tiger blending into savanna grass, or even a hunter merging with the Alpine terrain. Landscape is then sensed not as a static "container" of objects but as a momentary whole—a sensory event where fragments of sound, scent, and sight collide with one’s inner being to form a temporary, subjective “truth.”

Translation editor: Dr. Eglė Bazaraite

Instant_Dystopian is an attempt to understand where I am.

I’ve always been fascinated by instant cameras—maybe because I grew up with Kodak film, with its soft textures and the strange joy of not knowing exactly what the photograph would reveal. The waiting, the surprise, the occasional disappointment. Sometimes the images came out completely frozen or unreadable. Other times, they produced small photographic pearls—moments of unexpected beauty that seemed impossible to repeat. I was drawn to that unpredictability, to the randomness of catching a moment without full control. It felt more like witnessing than capturing.

That fascination stayed with me. Over time, even as I developed a practice centered on drawing—especially in charcoal—that desire to embrace uncertainty never left. When I returned to photography through instant cameras, I wasn’t looking for technical precision or perfect composition. I was looking for a way to reconnect with that intuitive gaze, the one that doesn’t plan but reacts. The process became immediate, physical, even childlike—less about taking a photo and more about letting one happen.

Shooting this way became essential, especially as I found myself moving through unfamiliar places, living far from home. These photographs help me orient myself. They act as markers, as tools to read the emotional and physical landscapes I pass through. Each image is a reaction—a raw and impulsive note in a longer process of seeing. They also bleed back into my drawing practice, not just as references, but as emotional starting points. The textures, the atmosphere, the imperfections—all of it informs how I build a drawing.

That’s how Instant_Dystopian was born. It’s not a formal project in the traditional sense, but more of a visual diary—a fragmented and urgent attempt to trace the geography around me. It’s not about producing beautiful or technically impressive images. It’s about being present, about responding to a place with honesty and curiosity. Each photo is part of an inner dialogue, shaped by the tension between the desire to understand and the feeling of being perpetually out of place.

Maybe this series is the spine of what I do. It holds together the different pieces of me—as an artist, and as a person trying to make sense of what it means to live away from home. Through the fragile, imperfect lens of instant photography, I’m not looking for answers. I’m just trying to stay connected—to place, to time, to something real.

You can find the full collection of these images on Instagram at @instant_dystopian, where I share the ongoing journey in its totality.

Jorge da Cruz

My Integration Documents: A Poetic Geography of Memory, 2010

In a city shaped by its latitude and mood, Jorge Da Cruz has found a terrain that mirrors the layered qualities of his work. Berlin—its stark winters, clouded skies, and ephemeral light—forms the atmospheric backdrop to “My Integration Documents”: A Poetic Geography of Memory, 2017, a project that moves between autobiography, political reflection, and visual poetry.

Da Cruz arrived in Berlin during one of those dark, heavy seasons, when sunlight rarely breaks through the dense cover of clouds. He had come from Lisbon, departing from the Lisbon harbor. But rather than resist the gloom of his new surroundings, he absorbed it. The city’s quiet greyness, its slow rhythm, and its fragmented transitions between seasons became central to his artistic language.

Integration Documents was created primarily through photography, using a Lomo, a Diana++, and several instant cameras. These tools, with their distinctive textures and imperfections, echo the project’s themes of memory, impermanence, and emotional geography. Berlin’s climate, with its sharp shifts and subdued light, doesn’t merely frame the work—it shapes it.

Decomposition Documents begins with a personal memory: a photograph taken in front of a gelateria in Barcelona, where the first ideas for the project began to form. This was Da Cruz’s first holiday after moving to Berlin—a moment of pause that allowed him to look back on his early days in a new country. The image, like many in the series, is casual, imperfect, and full of presence. Shot with a low-cost DIANA+ plastic camera, the photographs carry a soft distortion—grainy, tender, and unscripted. They capture seconds, not scenes.

What emerges is a visual essay on memory—its fragility, its interruptions, its permanence. The photographs and drawings in the series do not illustrate; they evoke. They function as visual footnotes to a broader narrative about migration, belonging, and the slow accumulation of personal and political weight.

In recent years, Da Cruz’s reflections have become increasingly shaped by the social and ideological tensions of our time. As far-right movements gain momentum across Europe, the emotional and psychological dimensions of integration—already complex—take on new layers. “

My Integration Documents” is not a direct political statement, but it carries within it the silent pressure of these realities. It suggests that memory and place are never neutral—that even the smallest moment is shaped by the world around it. This work also includes 20 paper works—objects that merge image and text, fragment and thought. They do not seek to explain but to accompany. Loosely structured, they resist narrative closure. Each piece feels like a private note made public, inviting the viewer to sit with uncertainty, with longing, with things unfinished.

At its core, “My Integration Documents” is not only about Berlin, nor solely about Da Cruz’s personal story. It is about the spaces between—between countries, languages, moods, and selves. It is a portrait of movement and stillness, of what we remember, and of what refuses to fade.

Berna Valada, Lisbon 2017

Seeing Through the Charcoal: On the Work of Jorge da Cruz-Jule Graf

Framing the picture—framing the view. In Jorge da Cruz’s charcoal drawings, this idea becomes more than just a visual device. His work invites us to reflect on how we perceive the world—not just through our eyes, but through memory, emotion, and the quiet architecture of our inner life.

The scenes he creates often feel suspended in time—neither fully here nor fully gone. Figures, spaces, and thresholds emerge through layers of shadow and light, always slightly out of reach. The charcoal medium, with its soft textures and deep blacks, allows for ambiguity. Edges blur. Surfaces breathe. Absence becomes as present as what’s depicted.

Da Cruz doesn’t try to show us everything. His images are intentionally limited, pared down, framed by silence as much as by form. There’s a sense of distance—not a physical one, but an emotional or psychological space. These drawings feel like memories resurfacing, or feelings we can almost name.

Rather than leading us toward a specific narrative, his work opens up a space for pause. For looking slowly. For noticing what’s just beyond clarity. A doorway, a wall, a horizon line—simple elements charged with meaning. His drawings don’t tell us what to see; they ask us to pay attention to how we see.

In this way, Jorge da Cruz’s charcoal works are less about representing the visible world and more about evoking the experience of perception itself—fragile, shifting, and deeply human.

@jorgedacruzinthestudio

“Bridges Between Cultures”

Introductory Remarks for the Exhibition Opening of Jorge da Cruz

Munich, 19 July 2011

by Christine Hubenthal

Jorge invited me to say a few words at the opening of this exhibition. That is, of course, a great honor for me – thank you!

I’d like to take this opportunity to tell you about the place where most of the works Jorge is showing here were created: South India, Tamil Nadu.

I lived in India from 2005 to 2007, working in agriculture. On one trip, I visited Pondicherry, where – quite unexpectedly – a Portuguese man sat down at my café table. We started talking. It was Jorge Cruz, who told me he was a painter and had come to Pondicherry with a grant from the Portuguese Ministry of Culture to work on a project titled “Utopia et Matter” – Utopia and Matter, or material.

He invited me to his studio, and from that point on, I spent a lot of time there, watching him work. I was able to witness the entire process of how his paintings came into being.

Jorge had set up his studio in a bamboo hut on the beach, covered with a thatched roof. The front was completely open – no glass, just open air. Because of the deep overhang of the roof and the lack of windows, it was fairly dark inside – which was a blessing, as the sun usually blazed down from the sky.

Jorge hadn’t brought any materials from Europe; he had arrived with just a backpack. He wanted his work to emerge from whatever he would encounter locally. The first phase of his project was purely research. In his search for canvases, he met an Indian artist who ended up building all his canvases and with whom Jorge exchanged a lot of ideas.

Color, painting, and pigments play an important role in public life in South India. Jorge spent a lot of time walking through the streets, observing people going about their daily routines, always on the lookout for materials and painting techniques for his work.

In front of many houses, you find beautiful drawings made with pigments, drawn in a specific sprinkling technique. They are a sign that the house has been cleaned – completely ordinary, part of daily life. Similarly, windshields of buses, cars, and rickshaws are often adorned with intricate designs; they have been blessed for the journey.

Many women wear a red dot on their third eye and another one at the hairline on the forehead. The one on the third eye is purely decorative, while the one at the hairline signifies that the woman is married and therefore not available. Some men and women have shaved heads and yellow-painted scalps – the result of a Hindu ritual. Some men wear the red Shiva stripe across the forehead.

All these observations found their way into Jorge’s paintings in one way or another – often transformed, stripped of their original function, repurposed. He used temple colors, pigments, henna, stickers, and stamps, as well as the traditional sprinkling technique that women use when the household cleaning is done.

I invite you to take a close look at the paintings and go on a journey of discovery to find these elements.

Many of Jorge’s works depict deities or religious symbols. I myself was deeply moved at the time by the natural and unquestioned presence of spirituality that I observed in Tamil Nadu – and in other parts of India as well. In Europe, we often seem unsure about how to deal with spirituality; I often experience the approach as strained or awkward. Some people even seem to lose their grounding.

In South India, on the other hand, spirituality is the most natural thing in the world. The first question, after “What is your name?”, is often “What is your god?”. Once, I replied that I didn’t have a god. I shouldn’t have said that – you must have a god of some kind. That much was clear from the concerned reaction of the person asking. From then on, I always said I was Christian – which was accepted without hesitation.

That didn’t stop anyone from taking me into temples or placing the red dot on my forehead. I even saw Muslim women in burkas celebrating Christmas in a Christian church – entirely natural, completely everyday.

Looking at Jorge’s paintings, I can see that he, too, was deeply impressed by this ever-present spirituality and the incredible tolerance we were fortunate to experience in South India.

Jorge’s approach – incorporating cultural research, painting techniques, and local materials into his work – makes his paintings incredibly exciting, in my view. I see them as a kind of collage of all the experiences and discoveries he made. In many places, his works clearly bear the marks of that story.

Even though Jorge ordered 90×90 cm square canvases from the painter Gobi, none of them actually had those exact dimensions, and very few had a true right angle. They were the product of real craftsmanship, made with the simplest tools.

All the frames were also made locally – in a small shop that was packed to the ceiling. After we brought the paintings there to be framed, the place was overflowing. To pack the paintings for shipping to Lisbon, we had to use the sidewalk in front of the shop – right in the middle of crowds of pedestrians passing by.

So many of these challenges were part of the painting process itself and are, in a way, essential elements of the work.

Now I’ve told you about South India. But the other works in this exhibition were also created as “traveling art.” Before Jorge decided to set up a permanent studio in Berlin, he worked exclusively through artistic residencies – turning the lack of a studio into a strength.

What strikes me most is how much the context of creation influences his paintings.

And now, I’ve said enough. Enjoy discovering this exhibition!

“Ponts entre Cultures”

Einführende Worte zur Ausstellungseröffnung von Jorge da Cruz, München, 19. Juli 2011

von Christine Hubenthal

“Jorge hat mich dazu eingeladen, bei der Eröffnung dieser Ausstellung etwas zu sagen. Das ist natürlich eine große Ehre für mich! Danke!

Ich möchte die Gelegenheit nutzen, um Ihnen von dem Ort zu erzählen, wo die meisten der von Jorge hier ausgestellten Arbeiten entstanden sind: Südindien, Tamil Nadu.

Ich habe von 2005 bis 2007 in Indien gelebt und dort in der Landwirtschaft gearbeitet. Bei einer Reise kam ich nach Pondicherry, wo sich unerwartet ein Portugiese an meinen Café-Tisch setzte. Wir kamen ins Gespräch. Es war Jorge Cruz, der mir erzählte, dass er Maler sei und dank eines Stipendiums des portugiesischen Kulturministeriums nach Pondicherry gekommen sei, um dort zum Thema „Utopia et Matter“ – also „Utopie und Materie, oder Material“ – zu arbeiten.

Er lud mich in sein Atelier ein, wo ich ab diesem Zeitpunkt viel Zeit verbrachte, um Jorge beim Arbeiten zuzusehen. Ich konnte also den gesamten Entstehungsprozess seiner Bilder mitverfolgen.

Jorge hatte sein Atelier in einer mit Strohdach abgedeckten Bambushütte am Strand eingerichtet. Vorne war sie offen – also ohne Glas, einfach offen. Durch das fensterlose und recht weit vorstehende Bambusdach war es ziemlich dunkel in dieser Hütte: ein Segen, denn die Sonne brannte meistens mit voller Wucht vom Himmel.

Jorge hatte aus Europa keine Materialien mitgebracht und war nur mit einem Rucksack angereist. Er wollte seine Arbeit aus dem entstehen lassen, was ihm vor Ort begegnen würde. Die erste Arbeitsphase für sein Projekt bestand eigentlich nur aus Recherche: Auf der Suche nach Leinwänden lernte er einen indischen Künstler kennen, der ihm all seine Leinwände baute und mit dem sich Jorge viel austauschte.

Farben, Malereien und Pigmente spielen eine wichtige Rolle im öffentlichen Leben in Südindien. Jorge verbrachte viel Zeit damit, durch die Straßen zu wandern und die Menschen bei der Verrichtung ihres Alltags zu beobachten – immer auf der Suche nach Materialien und Maltechniken für seine Arbeit.

Vor vielen Häusern finden sich wunderschöne Zeichnungen, die mit Pigmenten in einer ganz bestimmten Rieseltechnik gemacht werden. Sie sind ein Zeichen dafür, dass das Haus geputzt wurde – ganz normal, völlig alltäglich. Ähnlich sind auch die Windschutzscheiben vieler Busse, Autos und Rikshas mit kunstvollen Zeichnungen versehen – sie wurden für die Fahrt gesegnet.

Viele Frauen tragen einen roten Punkt auf dem dritten Auge und einen oben auf der Stirn am Haaransatz. Der auf dem dritten Auge ist nur Schmuck, der am Haaransatz dagegen ein Zeichen dafür, verheiratet und demnach bereits vergeben zu sein. Manche Männer und Frauen sind kahlgeschoren und haben den Kopf gelb bemalt – das Resultat eines hinduistischen Rituals. Manche Männer tragen den roten Shiva-Streifen auf der Stirn.

All diese Beobachtungen haben auf die eine oder andere Art Eingang in Jorges Bilder gefunden – oftmals entfremdet und ihrer Funktion entledigt, umfunktioniert. Tempelfarben, Pigmente, Henna, Aufkleber und Stempel hat Jorge ebenso verwendet wie die traditionelle Rieseltechnik, die die Frauen nutzen, wenn sie die reinigenden Hausarbeiten beendet haben. Ich möchte Sie einladen, sich die Bilder von Nahem anzusehen und auf Entdeckungsreise nach diesen Elementen zu gehen.

Viele von Jorges Bildern zeigen Gottheiten oder religiöse Symbole. Ich selbst war damals tief berührt von dem selbstverständlichen Umgang mit Spiritualität, den ich in Tamil Nadu – und auch in anderen Teilen Indiens – beobachten konnte. In Europa können wir mit Spiritualität offensichtlich nicht viel anfangen; den Umgang damit empfinde ich oftmals als verkrampft. Manche verlieren dabei die Bodenhaftung.

In Südindien dagegen ist Spiritualität das Normalste überhaupt. Die erste Frage nach „What is your name?“ ist oftmals „What is your god?“. Einmal habe ich darauf geantwortet, dass ich keinen Gott habe. Das hätte ich nicht tun sollen, denn irgendeinen Gott muss man schon haben – das zeigte mir zumindest die besorgte Reaktion des Fragenden. In Zukunft sagte ich immer, ich sei Christin – womit sich alle zufrieden zeigten. Das war aber kein Hindernis dafür, dass ich in verschiedene Tempel mitgenommen wurde und mir auch der rote Punkt auf die Stirn gemacht wurde. An Weihnachten habe ich muslimische Frauen in Burka in einer christlichen Kirche Weihnachten feiern gesehen – völlig selbstverständlich, alltäglich.

An Jorges Bildern kann ich erkennen, dass auch er tief beeindruckt war von dieser allgegenwärtigen Spiritualität und der unglaublichen Toleranz, die wir in Südindien erleben konnten. Jorges Ansatz, die Recherche über Kultur, Maltechniken und lokale Materialien in seine Arbeit zu integrieren, macht aus meiner Perspektive die Arbeiten unglaublich spannend. Ich sehe Jorges Bilder wie eine Collage aus all dem Erlebten und Gefundenen. Und an vielen Stellen sind die Arbeiten deutlich von dieser Geschichte gezeichnet.

Obwohl Jorge beim Maler Gobi Leinwände mit dem Maß 90×90 cm – also ein Quadrat – bestellt hat, hat keine der Leinwände wirklich diese Abmessung, und nur wenige tatsächlich einen rechten Winkel. Sie sind eben das Produkt echter Handarbeit, mit einfachsten Mitteln hergestellt. Auch alle Rahmen sind vor Ort gebaut – in einem kleinen Laden, der bis obenhin vollgestellt war, nachdem wir seine Bilder dorthin gebracht hatten, um sie rahmen zu lassen. Um die Bilder für den Transport nach Lissabon zu verpacken, mussten wir den Bürgersteig vor dem Laden nutzen – mitten zwischen Massen von Fußgängern, die ständig an uns vorbeispazierten. Viele solcher Herausforderungen gehören also mit zum Entstehungsprozess der Bilder – und sind deshalb essentieller Bestandteil der Arbeit selbst.

Nun habe ich Ihnen also von Südindien erzählt. Aber auch die anderen hier ausgestellten Arbeiten sind als „reisende Kunst“ entstanden. Bevor sich Jorge dafür entschieden hat, ein festes Atelier in Berlin einzurichten, hat er ausschließlich im Rahmen von artistic residences gearbeitet – und auf diese Weise die Not, ein Atelier zu haben, zur Tugend gemacht. Für mich besonders bezeichnend ist, wie sehr die Entstehungskontexte seine Bilder beeinflussen.

So, und nun habe ich genug erzählt. Viel Spaß beim Entdecken dieser Ausstellung!

Christine Hubenthal, Munich 2011

Ponts entre les cultures"

Jorge da Cruz Opening - July 19th, 2011 - 18 hours

In the foyer of the European Patent Office in Munich.

“The title provides a rather concrete impression about the character of the works exhibited. Two worlds are combined with regard to their symbols, to their typical elements, they are bridged and communicate with each other regardless of the real political or theological positions. The visitor is invited to think about on a global level and to follow up new ideas, confrontations and relationships.:

Jorge da Cruz, born in Lisbon, studied art in the Portuguese capital as well, then opened up to a more complex view by travelling through different parts of the world. Currently he used to live in Berlin.

His interest focusses on Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Shivanism - on the teachings and symbols of all principal religious teachings in the European and Asian world. His media style combines a Shiva deity with the cross, arrows with animals of Hinduism. His collages are dominated by a centralised composition, The rough brush stroke and the contours - partially and irregularly covered by colour - remind us of the wall paintings in Stone Age or of contemporary developments.

The alignment of various symbols or parts of them in stripes beside each other point to experiences with films and help to establish an advanced type of composition.

It is also up to the visitor to discover the bridges and to consider the novel and surprising relationships. "

„Ponts entre les cultures“

Jorge da Cruz – Ausstellungseröffnung am 19. Juli 2011, 18 Uhr

Im Foyer des Europäischen Patentamts in München

„Der Titel vermittelt bereits einen recht konkreten Eindruck vom Charakter der ausgestellten Werke. Zwei Welten werden in ihren Symbolen und typischen Elementen miteinander verbunden, überbrückt und treten miteinander in Dialog – unabhängig von realen politischen oder theologischen Positionen. Die Besucher sind eingeladen, global zu denken, neuen Ideen, Konfrontationen und Beziehungen nachzuspüren.

Jorge da Cruz, geboren in Lissabon, studierte auch in der portugiesischen Hauptstadt Kunst, öffnete sich jedoch durch Reisen in verschiedene Teile der Welt einem vielschichtigeren Blick. Derzeit lebt er in Berlin.

Sein Interesse gilt dem Buddhismus, Christentum, dem Islam, dem Shivaismus – also den Lehren und Symbolen aller bedeutenden religiösen Strömungen Europas und Asiens. Seine mediale Ausdrucksform verbindet etwa eine Shiva-Gottheit mit dem Kreuz, Pfeile mit Tieren des Hinduismus. Seine Collagen sind geprägt von einer zentralisierten Komposition. Der grobe Pinselstrich und die nur teilweise und unregelmäßig mit Farbe überzogenen Konturen erinnern an Wandmalereien der Steinzeit oder auch an zeitgenössische Strömungen.

Die Anordnung verschiedener Symbole oder deren Fragmente in Streifen nebeneinander verweist auf filmische Erfahrungen und eröffnet eine neue Form der Komposition.

Auch dem Besucher obliegt es, diese Brücken zu entdecken und die neuen, überraschenden Beziehungen zu erkennen.“

Hermann Schifferer,

Präsident des Kulturclubs am Europäischen Patentamt

On board at „Raumfähre“ Portuguese artist Jorge da Cruz Portrait and Interview by Sarah Zimmermann, Kassel - Berlin 2015

vivars.com

The biography of Jorge da Cruz sounds like a typical artist biography, Born and raised in a Lisbon suburb, he discovered his passion for art at an early age. To please his parents, he initially began a “down-to-earth” course of study, which he later abandoned in favor of art. After studying at Lisbon’s Ar.Co – Center for Art and Visual Communication – he quickly began working on his own projects. In the absence of a permanent studio,

Sarah Zimmermann

Jorge da Cruz has spent the past decade focusing on so-called “artistic residencies” – constantly changing homes, constantly changing studios. He has lived and worked in Portugal, Brazil, Morocco, India, and Germany. Like a chameleon, he adapts to his surroundings. Even more: he blends these constantly shifting environments into his work. His paintings act as mirrors of the places and contexts in which they’re made.

Against this background, the wide and sometimes contradictory use of color, forms, and symbols in his work begins to make sense. The artist’s images shift just as he – and the places he inhabits – do. “Travelling Art” is the term Jorge da Cruz uses to describe his own practice.

After many years of movement and searching, Jorge – at least for now – seems to have arrived somewhere. Since 2011, the 39-year-old has been living in Berlin. Under the name Kollektiv Raumfähre, he shares a studio space with other artists in the legendary Kunstquartier Bethanien at Mariannenplatz.

Da Cruz values the atmosphere and the sense of community there – even though each artist mainly works on independent projects. Twice a year, Bethanien opens its doors for an open house, during which a large group exhibition is prepared in advance. In Jorge’s opinion, Berlin is a very art- and artist-friendly city – not just because it’s relatively affordable, but more importantly, because it brings together so many other creatives.

Although Jorge da Cruz is an artist through and through, there is something linear and technical in his art. Fascinated by architecture and technical drawings – where every little centimeter is accounted for – he begins every work with a precise, structured sketch.

His art brings together two worlds: the accuracy and discipline of technical drawing and the freedom and unpredictability of artistic expression. To share his work, da Cruz often pursues new and unconventional approaches. One of these is “Art by Mail.”

As an alternative to traditional gallery exhibitions, he occasionally sends out his work by post: art prints in postcard format. He includes a short explanatory text and background on the piece. The recipient can then choose to keep it, forward it, or even purchase the original drawing.

Jorge da Cruz also maintains a strong connection to his hometown, Lisbon. There, too, he’s created a small but unique art project: when he’s not in town himself, he sublets his apartment to culturally curious visitors who can explore the city through the artist’s own suggestions and recommendations.

Interview

VIVARS.COM: Would you please briefly introduce yourself? Where do you come from, what stage are you at currently, and – metaphorically speaking – where do you want to go? Do you have a life philosophy?

JORGE DA CRUZ:

I was born in Lisbon, Portugal, and over the past years, I’ve lived and worked all over – Spain, India, Brazil, Morocco, Kassel :-). Since 2011, I’ve had a studio in Berlin. Right now, I’m in a very exciting phase in my career – a time of settling down in a city, collaborating with other artists… a very creative period indeed!

My life philosophy might be: “Discover what you love doing, what truly makes you happy, and have the courage to do it for the rest of your life.”

V: If you could describe your art in three sentences – or even just three words – what would you say?

JDC:

Physical, raw, instinctive.

V: Regarding your creative process: how do you work? Do you follow any repetitive patterns?

JDC:

Yes. Repetition and daily routines are super important to me. I always start any painting or video installation with a drawing. From there, the process evolves naturally and becomes a series of events that change the final composition.

V: What are your sources of inspiration?

JDC:

I’d rather talk about motivation than inspiration. Inspiration feels too esoteric to me. I always have the urge to paint, but I don’t always feel motivated to do it. That’s where discipline comes in. Even when I don’t feel like it, I keep going. That’s the work. I think it has more to do with commitment than inspiration.

I also love working in close collaboration with other artists – with writers, or with other visual artists like Ivo do Carmo, Frediano Bortolotti, and more recently, Carolin Schmidt. Teamwork in art is great – it can be the perfect motivation.

V: What do you consider your most important work? Which piece has special meaning to you, and why?

JDC:

I think the work I’m most attached to is a group of three paintings called Half of Leaf (3 x 80x100, oil pastel and henna on wood canvas). I created it in three different places and at different times: Lisbon in 2006, Fez in 2007, and Kassel in 2009.

Maybe it means so much to me because each piece reflects a very important phase in my life. The paintings are now exhibited in a restaurant in Berlin. If you come to Berlin, check it out – Elsenstr. 30b!

V: You chose Berlin as your base. Was that a conscious decision? How does the city and its environment influence your work?

JDC:

It happened by chance. It was a conscious decision, but not one I had planned. The environment has a huge influence on me. I lived in Kassel for two years and had a beautiful studio in the “Nordstadt,” with all the right conditions – but I simply couldn’t work there. Kassel was too clean, too orderly, too quiet.

Then I came to Berlin, and suddenly my work evolved rapidly. That showed me: I need more chaos and disorder to create. Big cities are perfect for me. So far, Berlin has been a paradise for making art. Kassel, on the other hand, is a good place to think and reflect – which I sometimes need, too. It will always be in my heart: friends, peace, and space to think.

V: As an artist, art is clearly central to your life. But do you ever need an “art time-out”?

JDC:

I don’t really take breaks from art. I live completely for it. Maybe the only thing that pulls me out of the studio is spending time with friends and family.

V: What do you think of vivars*?

JDC:

I wasn’t really surprised when I heard about vivars! I met the initiator while living in Kassel – it was through the project Dorf-Eigen-ART, where Sylvia Kernke was very active. I could already tell she would go on to realize more cultural and artistic projects.

I really like the idea of vivars. Of course, as with any online project, its success depends on the people who use it.

Kassel, 2014

Heidrun Hubenthal

Einführende Worte zur Ausstellungseröffnung Jorge da Cruz – 2012, Buchoase in Kassel

„Paradise open on Sundays or enclosure destined to have a prosperous life“

„Das Paradies hat sonntags geöffnet“ ist der Titel eines Textes von Ivo do Carmo, einem portugiesischen Philosophen, Literaten und Freund von Jorge, der noch in diesem Jahr in Portugal als Buch erscheint.

Die beiden Freunde sprachen oft über den Text, und Ivo beschreibt diesen Diskurs so:

„Über all das sprachen wir oft, Jorge und ich. Ich begab mich auf die Suche nach Worten. Er hielt Bilder fest.

Später stellten wir fest, dass in seinen Bildern meine Worte aufgehoben waren und meine Texte seine Bilder in sich trugen.

In diesem Zusammenspiel gegenseitiger Einsichten sah ich, wie das Paradies sich auf seiner künstlerischen Baustelle veränderte.

Ich beobachtete Jorge auf dieser Baustelle, wie er vermaß, zersägte, malte, zerstörte, ausprobierte und das Paradies erschuf.

Durch seine Arbeit, die hier ausgestellt ist, konnte ich meine eigene besser verstehen – und an sie glauben.

Danke.“

Jorge hat sich in seinen Bildern mit den ersten zwei Kapiteln von Ivo do Carmos Text beschäftigt.

Zitat aus dem Text von Ivo do Carmo

„Eine Gesellschaft aber, die darauf basiert, dass die Arbeit den Weg zum Seelenheil darstellt, braucht auch für das Paradies einen plausiblen Bedeutungsrahmen.

Waren einst der Himmel und die himmlischen Bilderwelten Teil der eschatologischen Semantik, sind diese Paradigmen heute machtlos gegenüber der Erlösungsmacht von Freizeitvergnügen und Tourismus.

Sie ahmen heute himmlische Verheißungen auf Erden nach.

Die Tourismusindustrie hat sich wohlklingende Worte wie „Himmel“, „Paradies“, „Traum“ oder „Wonne“ zueigen gemacht, die jedem verführerische Angebote geloben, der über entsprechend freie Zeit verfügen kann.Ob mit tropischen Stränden oder Bergen, Hotelzimmern oder Öko-Bungalows, Kreuzfahrten oder Wüstendurchquerungen, Naturparks oder Casinos – all diese Reiseprospekte appellieren an Seelenwünsche.

Und im Abglanz dieser kaleidoskopischen Bilder von Sinnlichkeit und Glück findet sich die Seele getrennt von ihrem Trugbild durch ein Ticket oder eine Postkarte.Die Analogie von Tourismus und Paradies geht weit über allegorische Affinitäten hinaus.

Das Wort Paradies kommt aus dem Persischen bzw. Avestischen pairi.daēza und bedeutet „umgrenzter Bereich“.

Stellen wir uns also eine prachtvolle Mauer um einen üppigen Garten vor, in dem anmutige Tiere durch exotische Vegetation streifen.

Wir sehen Brunnen und Seen, Statuetten und kunstvoll beschnittene Pflanzen,

und inmitten all dieses Gedeihens lustwandeln oder jagen Fürsten und Botschafter, stattliche Soldaten und illustre Reisende in ihrer Freizeit.Solch maßgebliche Paradiesvorstellungen unterscheiden sich nicht allzu sehr von heutigen Touristenressorts.

Das Ideal des Exklusiven, des Wohlbefindens und des Erlauchten sind Privilegien des Himmels auf Erden – abgestimmt auf die Seelenwünsche des Steuerzahlers.Aus all diesen Gründen repräsentiert der Tourist eine privilegierte Klasse,

denn er ist mobil, genießt die sinnlichen Freuden des Lebens,

und erkennt sich als Hauptfigur einer glücklichen Erzählung an.“

Jorge da Cruz’ Bilder stehen im Dialog mit diesem Text – und der Text ist eine Antwort auf die Bilder.

Die Ausstellung hat drei Teile

1. Das Paradies ist hier

Der Papagei als letzter Vogel des Paradieses in Beziehung zum Abendmahl – Leonardo da Vincis Abendmahl.

Die Babybilder mit Buddha und Flügeln unter dem Titel: Ein Freund erzählte mir, das Lächeln ist Gaza.

Die engelgewordenen verstorbenen Babys von Palästina.

Die Wiederkehr des Papageis im Spiegel des Meisters – Malereien, die sich mit dem Diesseits und Jenseits beschäftigen.

2. Der Druck auf alten Dokumenten: Ich liebte mein Leben dort

Eine Antwort aus dem Leben in einem sozialistischen Plattenbau.

3. Das Paradies hat sonntags geöffnet

Die Fotografien Sonnenuntergang in Jaffa, Sonnenaufgang in Tel Aviv und Der Sprung ins Wasser zeigen bereits die trügerischen Bilder touristischer Betrachtung.

Der Görlitzer Park als begrenztes Paradies

Die Zeichen der abgerissenen Häuser in Palästina an der Mauer – Einschluss und Ausschluss von Gegenwärtigem und Vergangenem.

Wie im Karussell drehen wir uns bei der Verfolgung des Paradieses im Kreis.

Um das Paradies festzuhalten, sind wir unterwegs mit Kameras und folgen den Icons – auch wenn es Ground Zero ist.

Wir schreiben Postkarten, lassen sie abstempeln und teilen unseren Liebsten mit, dass wir uns wünschen, sie wären auch hier.

Wir sind als Krieger und Kämpfer unterwegs, folgen Marken und Attraktionen.

Wir entspannen im Paradies und bewegen uns im Dreieck – als Tourist, der dem Zeichen folgt und die Attraktion sich einverleibt:

„Genießen Sie Traum-Temperaturen von 26 Grad an 365 Tagen im Jahr.

Entdecken Sie ein Stück Tropen auf 66.000 Quadratmetern mit dem größten Indoor-Regenwald der Welt,

Europas größter tropischer Sauna-Landschaft,

der Südsee mit 200 Metern Sandstrand –

und vielen Superlativen.“

Paradies ist der Ort, an dem der Traum von einer perfekten Insel in Europa wahr geworden ist.

Weitere Gedanken zum Thema Paradies

Die freie Zeit, die Muße, wird beschützt –

ob im Freizeit-Resort der Nazis „Kraft durch Freude“ im Seeküsten-Resort Prora,

oder im ummauerten Garten, der ein Innen und ein Außen hat –

und man sich fragt: Was ist die bessere Seite zum Leben?

So wie Adam und Eva, die in den Transparent-Zeichnungen aus dem Paradies geworfen werden,

weil sie den Regeln nicht gefolgt sind.

Und unsere postmodernen Paradiesversprechungen –

im Shoppingcenter oder in Ländern,

in denen wir als Touristen willkommen sind (als Geldsegenbringer),

aber als Meinungsäußerer sofort in Polizeigewahrsam genommen werden.

Unsere empfohlene Ausstattung:

Ein Handtuch,

ein Bademantel,

Sonnenbrille,

Sonnenschutzmittel,

Mut,

ein Ball,

nicht entflammbare Spielzeuge,

Taucherbrille,

Plastic Camera,

mehrere kleine Taschen – lieber als ein großes Gepäckstück.

All das, um den Traum zu verwirklichen:

eine tropische Insel mitten im Herzen Europas – 60 km von Berlin.

Inklusive: ein vorbestimmtes blühendes Leben.

Die Touristikindustrie verspricht ein schönes Wochenende in schöner Natur am Stadtrand –

eingeschlossen oder draußen, Lust oder Strafe.

Hainan Airlines wirbt mit exotischen Blumen und dem Papagei.

Der Künstler sagt:

„Bitte zeige mir ein Foto.

Bitte erzähle mir eine Lüge.

Bitte lass mich gehen.“

Auch das russische Paradies wird gezeigt – mit einem Parkplan und Neubauten.

Im christlichen Paradies erscheinen Adam und Eva im Bunker –

und zugleich im Liegestuhl zum Sonnen –

eingeschlossen oder hinausgeworfen,

mit dicker Jacke gegen die Kälte oder in ungeschützter Nacktheit.

„Und in Berlin zeigt sich dieses Haus wie ein großes Boot,

ein Kreuzfahrtschiff voll mit fremden Menschen,

die mehr wie Piraten sind in einem Land, wo alles funktioniert,

wo die Zeit angehalten ist,

und die einzige Bewegung die ist, von Boot zu Boot zu kommen.

Ein Land, wo Liebe abwesend ist,

wo das Lächeln keine Zähne hat

und das Abenteuer verloren gegangen ist in den Gängen der U-Bahn-Linie 1.“

Auch hier sind die Menschen auf der Suche nach dem Paradies.

Wir alle sind Eingeschlossene und Ausgeschlossene zugleich.

– Heidrun Hubenthal

Bethanien, ou a Máquina Cultural de Berlim

Entrevista por Joana Violante

Licenciada em Ciências da Comunicação e Mestre em Jornalismo de Rádio pela Universidade da Beira Interior, vive e trabalha em Berlim desde novembro de 2013.

Se a cidade de Berlim respira arte e cultura, o Bethanien é sem dúvida parte do seu sistema respiratório. Os pulmões da cidade, onde viver de arte é possível, assemelham-se a uma Berlim em ponto pequeno: carregados de história, várias nacionalidades, arte e cultura dos mais variados campos – e até paredes com graffitis. No meio desta máquina, há muitos portugueses.

A Instituição – uma história secular

A história do Bethanien remonta a 1847, quando o Rei da Prússia, Friedrich Wilhelm IV, mandou edificar um hospital desenhado por Theodor Stein. Para além do hospital com cerca de 500 camas, foi construído um instituto para a formação de enfermeiros e médicos e um orfanato.

Obra feita, o hospital manteve-se ativo durante mais de um século. A partir dos anos 60, fruto das consequências da Segunda Guerra Mundial e da Guerra Fria, o hospital começa a ter algumas dificuldades financeiras, prevendo-se já a impossibilidade de o manter. Tanto que, em 1969, recebe uma ordem de demolição.

Os protestos começam e o Bethanien consegue um estatuto de edifício protegido. No entanto, o fecho torna-se inevitável e acaba por acontecer um ano mais tarde, em 1970, altura em que é vendido ao Estado Alemão por 10,5 milhões de Marcos.

Começa a grande batalha de sobrevivência. Para evitar a demolição e a construção de habitações sociais no seu lugar, o edifício começa a ser ocupado por populares. A sua força fala mais alto: conseguem manter o edifício erguido e acordam com o Estado o seu uso legal para um projeto residencial de jovens.

A banda berlinense Ton Steine Scherben imortaliza estes momentos na música "Rauch Haus Song".

O Bethanien abre novamente as suas portas em 1973. Desde então, tem oferecido espaço para instituições culturais e artísticas. Para além do Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, existe ainda o BBK Berlin Printing Studio, estúdios, espaços para exposições, teatro e dança, a Escola de Música de Kreuzberg, entre outros.

Renasce assim um prédio, uma entidade, que se transforma no pulmão cultural de Berlim.

Bethanien e Gulbenkian – uma relação de sucesso

A formação de artistas e a vivência da arte é o papel fundamental desta instituição no Kottbusser Damm, que todos os anos recebe dezenas de novos artistas em residência, durante 6 a 12 meses.

Este programa de intercâmbio é uma plataforma para artistas de todo o mundo e dá a oportunidade de desenvolver e implementar um projeto, bem como consolidar a sua posição no cenário berlinense.

Portugal é um dos países que todos os anos “envia” um artista para este programa, através do protocolo existente com a Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (FCG). A parceria entre as duas instituições fará agora 15 anos.

Luís Gil, responsável pelo Apoio à Internacionalização e Gestor de Processos de Ação Distributiva de Artes Visuais da FCG, explicou à Berlinda como tudo começou:

“A parceria teve início com o extinto serviço de Belas Artes. Todos os anos, apareciam várias candidaturas para o Bethanien, para futuros artistas”, e por isso, decidiram avançar com a proposta de parceria.

Desde então, todos os anos a FCG recebe cerca de 50 a 60 candidaturas para a instituição alemã. Só é concedida uma bolsa, decidida por um júri de várias entidades artísticas através de um extenso processo de seleção.

Um dos critérios essenciais para obtenção da bolsa é a:

“Apresentação de um projeto original, que deve ir de encontro às necessidades artísticas do momento”, diz Luís Gil.

Escolhido o feliz contemplado, o vencedor tem a oportunidade de passar um ano em Berlim. Em todas as 14 bolsas já atribuídas, Luís Gil garante que o feedback é sempre:

“Extremamente positivo, como mostram [os artistas] no relatório final. Os candidatos realçam a renovação de ideias, o intercâmbio cultural e, claro, a experiência.”

O Bethanien como escritório oficial

Além de acolher bolseiros, o Bethanien também coloca ateliers à disposição de artistas que os queiram alugar. Encontrar uma vaga não é fácil, mas também não é impossível. A concorrência e a criatividade dos vários interessados é forte, por isso é preciso mostrar trabalho e uma certa realização.

Aqui não se brinca aos artistas – vive-se de arte e da sua profissionalização.

Sérgio Fernandes e Jorge da Cruz, respectivamente do teatro e da pintura, entraram para o Bethanien há cerca de quatro anos, e desde então ali têm o seu atelier permanente.

“O Bethanien estava a passar por uma alteração estrutural”, explicou Jorge da Cruz.

“Nessa altura todos os artistas que estavam em residência na cave passaram para um novo edifício na Kottbusser Straße, com mais condições de habitabilidade”.

O Bethanien decidiu “abrir concurso aos espaços e aos ateliers que ficaram livres”. Os dois artistas portugueses candidataram-se e foram aceites, sendo dos primeiros a entrar para esta “nova fase”.

Por esta altura, conta Sérgio, uma das ideias principais era:

“Equilibrar a variedade artística”

e

“Abrir este espaço a pessoas mais viradas às artes de palco”.

Entraram várias companhias, o Mimo Internacional Centro, o Instituto de Teatro, Sérgio e várias outras pessoas ligadas ao teatro. Abriu-se assim o Performance of Bethanien.

Jorge da Cruz – o artista plástico com um pé em Lisboa e outro em Berlim

Jorge da Cruz veio para a Alemanha em 2006. Antes tinha estado em Kassel durante alguns anos, onde realizou várias exposições. Cerca de quatro anos mais tarde, decidiu mudar-se para Berlim.

Aqui começou a trilhar o seu caminho para viver da Arte – algo que sabia ser impossível em Portugal:

“Desde que vim para cá comecei a expor e a vender. Ainda não vivo da pintura,

mas hoje posso dizer ‘ainda não vivo da pintura’ – algo impensável em Portugal.”

Com formação em Pintura e Desenho pela Ar.Co – Centro de Artes & Comunicação de Lisboa, considera que:

“Por ilusão ou estupidez, a pintura não é suficientemente direta

e não entra na vida das pessoas de uma forma forte.

As pessoas estão muito mais resistentes, menos disponíveis para se deixar entregar ou comover.”

Para remediar a situação, Jorge complementa as suas pinturas com vídeos, “nada técnicos” e sem “conhecimentos cinematográficos”, criando:

“Pinturas que se movem.”

“É quase como uma analogia daquilo que falta, ou que quase falta na pintura.

Para mim, a pintura tem que se mexer, tem que sair da tela e tocar nas pessoas.”

Com o tempo, o atelier deixou de ser apenas um local de trabalho e tornou-se uma espécie de “segunda casa”, partilhada com mais cinco amigos – todos artistas.

“É quase uma família que se junta ali todos os dias,

um sítio onde nós podemos ir com segurança e onde se respira arte.”

Este é o ambiente certo para o desenvolvimento artístico, diz Jorge, pois consegue ter ao mesmo tempo:

“Uma certa dose de isolamento e os artistas e amigos ao redor.”

Apesar do trabalho de Jorge ser desenvolvido em Berlim – e aqui poder quase viver da arte e da pintura –, o artista português não se considera um “emigrante típico”.

Tem um pé lá, em Lisboa, e o outro cá, em Berlim.

Vive de Lisboa, onde vai com frequência, mas trabalha em Berlim.

Um dia “gostava de voltar a viver em Portugal. Mas por enquanto é só férias.”

Texto: Joana Violante

Revisão: Inês Thomas Almeida

Bethanien, or Berlin’s Cultural Machine

Interview by Joana Violante

Graduated in Communication Sciences and with a Master’s in Radio Journalism from the University of Beira Interior, she has lived and worked in Berlin since November 2013.

If the city of Berlin breathes art and culture, then Bethanien is undoubtedly part of its respiratory system. These "lungs of the city," where living off art is possible, resemble a miniature Berlin: rich in history, home to various nationalities, and filled with art and culture across disciplines — even down to its graffiti-covered walls. Among this machine, many Portuguese artists have found a place.

The Institution – A Centuries-Old History

The history of Bethanien dates back to 1847, when King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia ordered the construction of a hospital designed by Theodor Stein. In addition to a 500-bed hospital, the facility included an institute for training nurses and doctors, and an orphanage.

Once completed, the hospital remained active for more than a century. By the 1960s, as a result of World War II and the Cold War, it began to face financial difficulties and was deemed unsustainable. In 1969, it was slated for demolition.

Protests followed, and the building was granted protected status. Still, closure became inevitable, and in 1970 it was sold to the German government for 10.5 million Deutsche Marks.

Then came the great battle for survival. To prevent demolition and the construction of public housing on the site, the building was occupied by locals. Their determination prevailed: the building was preserved, and an agreement was reached with the government to use it legally for a youth residential project.

The Berlin-based band Ton Steine Scherben immortalized the events in the song “Rauch Haus Song.”

Bethanien reopened its doors in 1973. Since then, it has provided space for cultural and artistic institutions. In addition to the Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, it houses the BBK Berlin Printing Studio, art studios, exhibition spaces, theater and dance venues, the Kreuzberg School of Music, and more.

Thus, a building was reborn — a cultural hub that became a vital part of Berlin's creative engine.

Bethanien and Gulbenkian – A Successful Partnership

Artist development and engagement with art is the core mission of this institution, located on Kottbusser Damm, which welcomes dozens of new resident artists each year for 6 to 12-month stays.

This international residency program serves as a platform for artists from around the world to develop and implement a project, as well as to establish themselves in Berlin’s art scene.

Portugal is one of the countries that annually “sends” an artist to this program, through a protocol with the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (FCG). The partnership between the two institutions is now in its 15th year.

Luís Gil, head of Internationalization Support and Distribution Process Manager for the Visual Arts sector at FCG, explained to Berlinda how it began:

“The partnership started with the now-defunct Fine Arts department.

Every year we received multiple applications for Bethanien from emerging artists.”

“So we moved forward with a partnership proposal.”

Since then, the FCG receives around 50 to 60 applications each year. Only one grant is awarded, determined by a jury made up of various artistic entities through a competitive selection process.

One of the essential criteria is the:

“Presentation of an original project that aligns with the current artistic context,” says Luís Gil.

The selected artist is then given the opportunity to spend a year in Berlin. Of the 14 grants awarded so far, Luís Gil affirms that the feedback is always:

“Extremely positive, as reflected in the artists’ final reports.

They consistently highlight the renewal of ideas, cultural exchange, and of course, the overall experience.”

Bethanien as an Official Studio Space

In addition to hosting grantees, Bethanien also rents out studios to artists. Finding a spot isn’t easy — but it’s not impossible. Competition is tough and creativity is high, so you have to show commitment and achievement.

This is not a place for playing at being an artist — here, art is a profession.

Sérgio Fernandes and Jorge da Cruz, from theater and visual arts respectively, joined Bethanien around four years ago and have had permanent studios there ever since.

“Bethanien was undergoing structural changes,” explained Jorge da Cruz.

“At the time, all resident artists in the basement were moved to a new building on Kottbusser Straße, with better living and working conditions.”

Bethanien opened applications for the vacant studios. The two Portuguese artists applied and were accepted — among the first to enter this “new phase.”

According to Sérgio, the main idea at the time was to:

“Balance artistic diversity”

and

“Open up the space to more performing arts professionals.”

New companies joined, including the Mimo International Center, the Institute of Theater, Sérgio himself, and other theater-related artists — giving rise to the Performance of Bethanien.

Jorge da Cruz – A Visual Artist With One Foot in Lisbon, the Other in Berlin

Jorge da Cruz moved to Germany in 2006. He had previously spent a few years in Kassel, where he held several exhibitions. About four years later, he moved to Berlin.

There, he began carving out a path toward making a living from art — something he knew wasn’t possible in Portugal:

“Since coming here, I’ve started to exhibit and sell.

I still don’t live off painting entirely —

but now I can say ‘I don’t live off painting yet’,

which would have been unthinkable in Portugal.”

With a degree in Painting and Drawing from Ar.Co – Center for Arts & Communication in Lisbon, he observes that:

“Out of either illusion or naivety, painting isn’t direct enough and doesn’t reach people in a powerful way.

People are more resistant, less willing to surrender or be moved.”

To address that, Jorge complements his paintings with videos — “non-technical,” “lacking cinematic expertise” — essentially creating:

“Paintings that move.”

“It’s almost an analogy for what’s missing — or nearly missing — in painting.

For me, painting has to move, it has to step off the canvas and touch people.”

Over time, his studio became more than just a workspace — it became a kind of “second home,” shared with five other friends, all artists.

“It’s almost like a family that gathers there every day —

a place where we can go and feel safe, where art is in the air.”

It’s the right environment for creative growth, says Jorge, as it offers:

“A balance between solitude and community.”

Although his work is based in Berlin — and he can “almost” live from his art — Jorge does not consider himself a “typical emigrant.”

He has one foot in Lisbon and the other in Berlin.

He draws life from Lisbon, which he visits often,

but his work is in Berlin.

One day,

“I’d like to live in Portugal again. But for now, it’s just for vacations.”

Text: Joana Violante

Editing: Inês Thomas Almeida

Ausstellung ”utopia x matter” im Café Buchoase, Germaniastr. 14, Kassel

Eroeffnung 17.07.2009 um 18:00 Uhr

Dauer der Ausstellung: 18.07.2009-26.08.2009

Jorge Cruz reiste im Jahr 2006 in das in Tamil Nadu (Südindien) gelegene Auroville. Dort lebte und arbeitete er drei Monate lang, recherchierte über Materialien, die vor Ort zum Zweck der Dekoration oder des religiösen Kultes genutzt werden. Hierbei stieß er auf eine große Vielfalt: von Stempeln über Gesichtsmalfarbe bis hin zu Tempelfarben sammelte er alles, was ihm begegnete.

Außerdem nahm er Kontakt mit einem indischen Künstler auf, Gobi. Dieser lebt in Auroville von seiner Malerei, die er an Touristen verkauft. Gobi baute alle Holzrahmen und bespannte sie mit Leinwand. Seine Rahmen stellen also die physikalische Grundlage Jorges Arbeiten dar.

Das Land Indien hat Jorge Cruz tief beeindruckt. Es machte ihm erlebbar, dass es nicht die eine Wahrheit, die eine richtige Handlungsmöglichkeit, die eine gute Religion, den einen richtigen Lebensweg, die eine richtige Hautfarbe, die eine richtige Kultur, die richtigen Werte gibt. Wer in Indien in Schwarz und Weiß unterscheiden möchte, ist zum Scheitern verdammt, wer sich dort in Ungeduld üben möchte, wird unglücklich, wer dort intolerant sein möchte, wird merken, dass er damit nicht weit kommt. In diesem Sinne stehen auch seine Beobachtungen über das Miteinander von Religionen, die dort so friedlich nebeneinander existieren. Was die Menschen alle gemein haben ist, dass sie religiös sind. Alle praktizieren ihre Religion aufrichtig. Doch ist dies kein Grund zur Trennung.

Die Arbeiten, die in Auroville entstanden sind, vereinen die lokalen Techniken der „alltäglichen, Malerei“ (also nicht etwa von Künstlern gemacht, sondern von ganz gewöhnlichen Menschen), die Jorge Cruz anzuwenden versuchte. Weiterhin nutzte er ausschließlich die lokalen Grundfarbstoffe und andere Materialien, die er in seiner Umgebung fand. Seine Arbeiten sind also eine Auseinandersetzung mit lokalen Materialien und Maltechniken. Für ihn sind sie Spiegel dieser toleranten Gesellschaft, der er in Südindien begegnete und die ihn schwer beeindruckt hat.

CH

“Paradise Opens on Sundays”An Analysis of the Work of Jorge da Cruz

Ivo do Carmo

“And on the seventh day He rested from all His work.”

Genesis 2:2