Bacchus and a Divine March

La Jeunesse de Bacchus is something else entirely

This Tattoo piece was chosen by @etions_formidables, the owner of the studio where I first began tattooing. It was right at the beginning of my time there — a period defined by nerves, excitement, uncertainty, mistakes, and learning. Her choice felt immediately right. Ancient celebrations, ecstatic rites, mythological abandon — these themes have always drawn me in. This painting holds all of that, but without spectacle for spectacle’s sake. It understands devotion as movement, not belief.

We placed the tattoo in one of the most demanding areas of the body: the back of the knee. I had heard the warnings. Everyone talks about the pain there. They weren’t exaggerating. But in a strange way, that intensity felt appropriate. The piece demanded something in return. Like the figures in the procession, it asked for endurance. It asked for surrender.

Because La Jeunesse de Bacchus isn’t just a mythological parade frozen in time. It’s a call. A reminder of something deeply human — the need to dance, to lose structure, to step outside logic and order, even if only briefly. To follow a rhythm without asking where it leads.

You don’t need to know the mythology to understand it. You only need to look.

The procession is still moving. The music hasn’t stopped. And this divine march — wild, radiant, unfinished — keeps going.

A march I know I’ll never stop walking.

nOT

La Jeunesse de Bacchus

is a procession that never really stops.

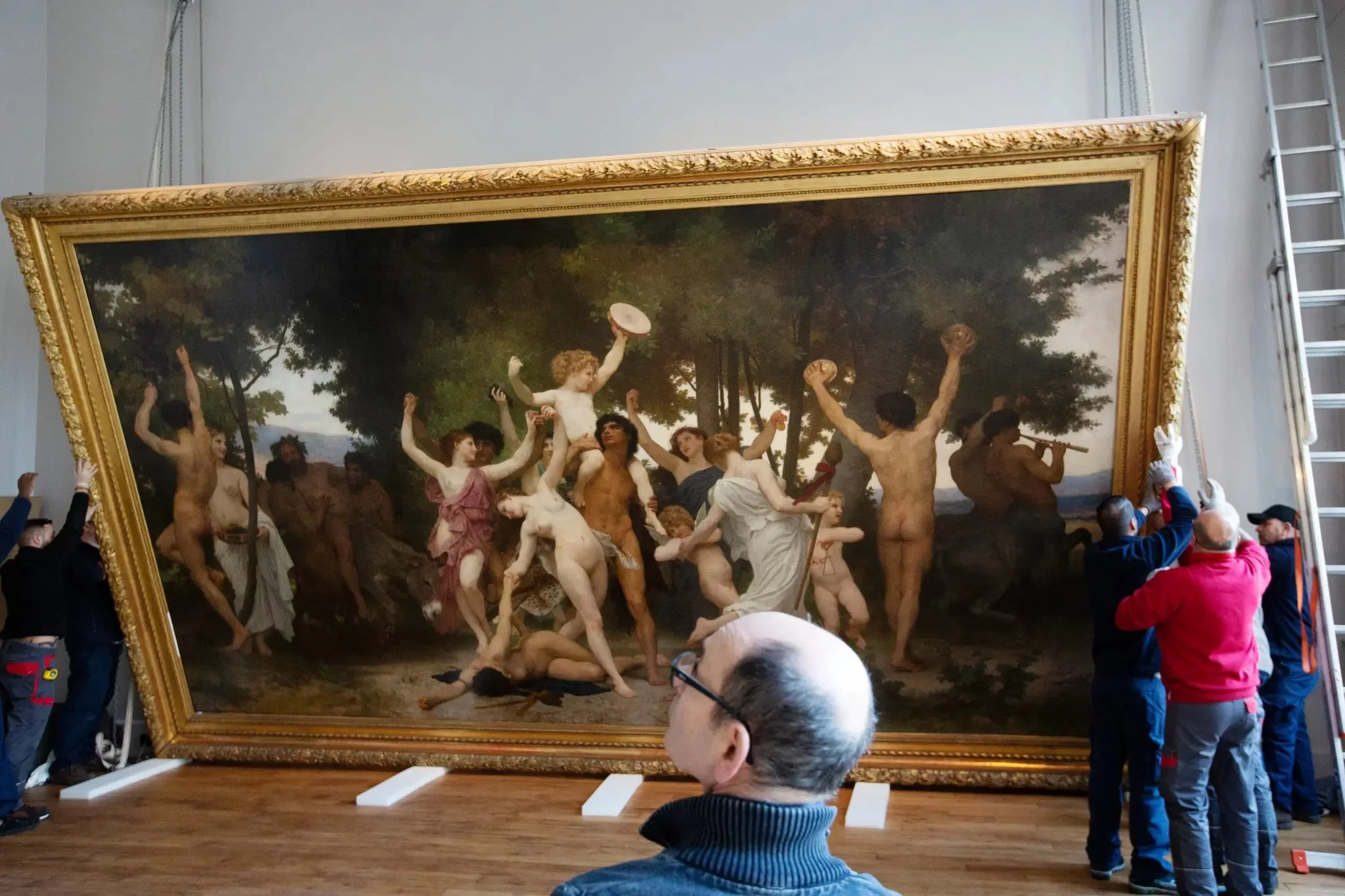

Bouguereau’s technique is flawless. Every muscle, every strand of hair, every bit of fabric — it’s all so carefully done you almost forget it's paint. You can feel the hours in each figure. And yet, the painting doesn’t feel frozen. It doesn’t show off. It moves. It breathes. Somehow, underneath all that discipline, something wild manages to break through. Like the canvas couldn’t fully contain it.

There’s a kind of freedom leaking through the edges. Not the loud kind. Not chaos. Just a quiet energy that keeps pushing forward. Like it knows something you don’t. Like it doesn’t want to be looked at — it wants to pull you in and carry you with it.

But for years, no one saw it.

Too big. Too theatrical. Too much for the walls and tastes of its time. So they rolled it up. Put it away. Let it fade into storage. Like it was too alive to deal with.

But a painting like this doesn’t disappear. Not really. It waits. It waits for the right eyes, the right moment, the right world to see it again. And when it came back, it didn’t need to shout. It just stood there, exactly as it always was — with the quiet confidence of something that never lost its power. Just its spotlight.

References:

Official Musée d'Orsay Page (where the painting is currently housed):

https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/jeunesse-de-bacchus-153183

(Includes high-resolution images, provenance, and museum notes.)Google Arts & Culture - La Jeunesse de Bacchus:

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/la-jeunesse-de-bacchus-william-adolphe-bouguereau/2wFWVTuVxOm89A

(Explore in ultra-high detail and zoom in on the figures and brushwork.)

Context, Symbolism, and Interpretation

Analysis by The Art Story Foundation – Bouguereau’s style and mythological themes:

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/bouguereau-william-adolphe/"The Return of Bouguereau" – Smithsonian Magazine:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-return-of-bouguereau-132713095/

(A look at Bouguereau’s fall from critical favor and resurgence.)

The Myth of Bacchus/Dionysus

Perseus Digital Library – Bacchus/Dionysus in Greek Literature:

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/searchresults?q=dionysus

(Explore original ancient texts featuring Bacchus/Dionysus.)Dionysus: Archetype of Ecstasy and Liberation (Encyclopedia Britannica):

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Dionysus

Bouguereau’s Artistic Legacy

Art Renewal Center – William-Adolphe Bouguereau Gallery:

https://www.artrenewal.org/artists/william-adolphe-bouguereau/6

(Extensive archive of his works in high resolution.)Bouguereau and the Academic Tradition (Metropolitan Museum of Art essay):

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/adac/hd_adac.htm